L eonardo da Vinci’s notes on human anatomy remained largely forgotten until the mid-18th century when the Scottish anatomist William Hunter learned of them in the royal collection. A new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland , called Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life, brings some of these drawings together with a variety of objects and artwork from the Scottish Enlightenment to illuminate the frequently tense relationship between the furthering of anatomical knowledge, and the need of early anatomists to procure dead bodies. Leonardo got around the problem by working with elite patrons and by assisting an academic professor of anatomy; later Dutch and Scottish anatomists often had to pull bodies from gibbets and graveyards.

Modern medicine, the art of postponing death, is built on a foundation of this grave robbery, but had its origins in a more collaborative, consensual attitude typified by Leonardo. It’s an approach that has now returned: the exhibition closes with a moving series of videos from Edinburgh’s current professor of anatomy, a medical student and a member of the public, each explaining the vital role of bequests by people who leave their body to medical science. Some of this history is unavoidably grisly: the exhibition resurrects the story of Burke and Hare, two Irishmen of Edinburgh who obtained bodies for the anatomist Robert Knox through the simple expedient of murdering them.

Burke’s fate was to be anatomised: on my way to tutorials in Edinburgh’s medical school I used to pass his skeleton, and it was a surprise to see it across the road in the museum. Burke’s signed confession has been loaned from the New York Academy of Medicine, and some detective work has unearthed details of the lives of his victims. There is Johan Zoffany’s painting of William Hunter lecturing, and from Amsterdam, Cornelis Troost’s three-metre The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Willem Röell – more ghoulish (and more accurate) than Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicola es Tulp , painted almost 100 years earlier .

One particularly striking exhibit is an early 19th-century petition, signed by 248 medical students, asking for bodies to be made available to them through legal means. In the winter of 1507-1508, Leonardo was in Florence, where he conducted a postmortem on a man who, shortly before dying, had claimed to be more than 100 years old; there are suggestions that he knew he was to be anatomised after death. Leonardo identified the cause of death as a narrowing of the coronary arteries, and made the first clinical description of cirrhosis of the liver.

By late 1510 he was in Pavia, a university city south of Milan, working with that city’s professor of anatomy on notes for a grand anatomical treatise. Pavia is cold in winter, ideal for the preservation of human remains, and many of his anatomical sketches derive from work completed through the winter of 1510-1511. Leonardo was never content with a representation of death without exploring how it might be animated by the dynamism of life His collaborator in Pavia, Marc’Antonio della Torre, died in 1511 of plague, which is perhaps why Leonardo set this work aside.

Or it may have been other personal and professional pressures – by the end of 1511 he was living in a villa east of Milan where he continued to make sketches not of human anatomy, but dogs, birds and the ways blood flows through the heart of an ox. In 1513 he was in Rome, trying to further his anatomical work in the hospital of Santo Spirito when a German mirror maker, who disapproved of human dissection, put a stop to it by reporting him to the pope. In 1516 Leonardo took up an invitation to move to France under the patronage of Francois I, and made his home at Amboise.

He took his anatomical notes with him and died there in 1519 without completing the treatise. How they came to be in Edinburgh is a story full of gaps: first, they fell into the hands of his companion Francesco Melzi (described by Leonardo’s first biographer Vasari as “a handsome boy and much loved by him”), then after Melzi’s death in 1570 they were sold to Pompeo Leoni, a sculptor who, on being commissioned by the king of Spain, carried them to Madrid. No one knows how they came to be in England in 1630 among the collection of Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel.

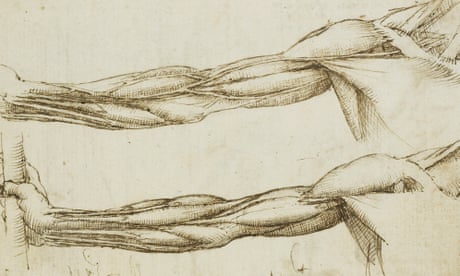

By 1690 they had been sold or gifted to the royal collection of William and Mary, where they have remained ever since. The bones of the foot and shoulder, studies of the heart and pulmonary vessels of an ox and the veins and muscles of the arm drawn by Leonardo da Vinci, c1510-11. Photograph: Royal Collection Trust Leonardo’s drawings borrow from the conventions of architecture in visualising anatomical structures from various perspectives.

We can get a glimpse of the great treatise he had in mind by examining that of the Flemish anatomist Vesalius, whose book On the Fabric of the Human Body (1543) was the first major anatomical work to overturn classical scholarship. Vesalius was a supreme dissector but unlike Leonardo didn’t make his own drawings, and his book is more concerned with form than with function. Leonardo’s approach was entirely different: he was never content with a representation of appearance in death without exploring how it might be animated by the dynamism of life – the scrawled notes, in his usual mirror writing, that surround these images probe relentlessly at the question: “But how does it work?” He knew, too, that life’s mechanisms were beyond the reach of his keen eyesight: “Nature is full of countless causes that never enter experience,” he wrote – an observation that remains true even today, when it is possible to visualise the mechanisms of life down to the molecular level.

The idea of thinking through drawing is there even in English – we speak of “figuring” things out. This exhibition shows us Leonardo puzzling over the disconnect between the reality he saw, and what earlier anatomists told him he should see. With the accompanying notes we can appreciate how the heart, for him, was not a muscular pump, but an organ to suffuse the blood with “noble” spirits.

The mesentery, a pleated skirt of fatty tissue in the abdomen (“sinewy and lardaceous” is how he memorably puts it) is the ligament that suspends the small intestine: my own university textbooks struggled to explain its structure, but Leonardo managed it. His drawings of the trachea envisage the way it changes shape during natural breathing, while the engineering principles of weight-bearing are made manifest in his oblique perspectives on the foot. Most of us move through tunnels of perception, seeing largely what we expect to see, but Leonardo worked hard against lazy expectation and his notebooks brim with unprecedented insights into nature, all drawn from first principles.

It’s a great pity his drawings weren’t publicised until the 1700s, but the exhibition illuminates how anatomists of the Enlightenment made up for lost time. It’s exhilarating to be taken on a 500-year journey through humanity’s evolving understanding of the body, from Renaissance Florence through to modern anatomical science in Edinburgh. Leonardo died before realising his treatise but these sketches live on, and every mark on them is a line of thought and attention, an interrogation of beauty.

Leonardo da Vinci’s life and work were animated by breadth of vision , intellectual curiosity, the adoption of alternative perspectives, and a fascination with elucidating the elegance of life from the wreckage of death – the same could be said of this exhibition. Gavin Francis is a GP in Edinburgh. His books Adventures in Human Being and Shapeshifters touch on the anatomical work of Leonardo da Vinci; his latest book is Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence (Wellcome) Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life is at the National Museum of Scotland until 30 October.